Malachi 3:1-4

Luke 1:68-79/Canticle 16 “Song of Zechariah”

Philippians 1:3-11

Luke 3: 1-6

Shag carpet. You remember it? Usually some fashionable color… gold, like the harvest-gold refrigerator, or dark brown that showed every single little piece of lint, or the horrid olive green, but shag carpet was the thing in the 70’s. It was the thing. Many of us here may not be old enough to remember shag carpet, so if you do not have a visual on this, ask some of us who are during coffee hour.

In the early 70’s, and in a fit of “Keeping up with the Joneses,” my mother decided to do a bit of remodeling to her small home in Olympia. She hired a friend to put up laminate paneling on one wall in the living room, and then… she carpeted the floor in that room, covering beautiful hardwood floors, with gold shag carpet. We couldn’t get over how fabulous it looked. It was “magazine” cool. It looked especially good after being vacuumed. That is, until you walked through it, and then all the carpet strands lay all higgeldy-piggeldy, rather like my son’s hair when he gets up in the morning. So I bought Mom one of those shag carpet rakes… it was like combing the carpet. It would make all the shag lay one way or the other or stand up – until someone walked through the room. It was great to use just before company came. You stood in the kitchen and looked into that living room. You didn’t go into it, you just looked, and the “wow factor” couldn’t be missed. Shag carpet is gone now, thankfully, and the irony of putting down a carpet that only looks good when you don’t walk on it – but you want it to look good for visitors – cannot be missed. Shag carpet was an extreme reflection of what seemed important in those days. Today it seems like a mystery not worth solving. And though there is a certain movement in the fashion world toward “retro,” I’m guessing we have long since seen the backside of shag carpet. It was an incongruous element in any home in which people walked.

John the Baptist, an incongruous character, was probably not an individual who would have prepared for visitors by doing any sort of menial sweeping or tidying up. John probably didn’t bake a loaf of bread or make any effort at welcoming anyone out to the wilderness, for it was his message that was far more important than how things looked or making people feel welcome. “Repent and Prepare!” John proclaimed.

Luke’s gospel doesn’t offer much in the way of description, but from Mark’s gospel, we learn that John wore camel hair, a leather girdle around his waist, and ate locusts and wild honey. So, though Luke doesn’t describe him, he does, by way of setting him in history, inadvertently tell us a bit about who he wasn’t. John wasn’t any of those powerful, wealthy individuals mentioned at the beginning of chapter 3 - Emperor Tiberius, Herod, Philip, Lysanias, Annas and Caiaphas. He was simply John.

He was just this one marginalized person on the border of society – no power, no wealth, but it was to him that the word of God came. More incongruity. John was, you see, called to be a prophet, and prophets often cause people to feel uneasy. He was an unlikely person in an unlikely place. He was a person from whom you and I might look away. A nobody. . . A nobody with a growing following.

And… the word of God came to John, not in Rome, not in Jerusalem, not even in a small village like Nazareth… no, not in the places of power, population, and wealth, but God sent the message to John out in the wilderness. In those days, the wilderness was considered a place of chaos and danger. Families wouldn’t just pack a picnic basket nor don their walking shoes to take in the beauty of nature in the wilderness like you and I might. No, at that time, folks only went into the wilderness if they needed to get through it – to get from point A to point B. But, many were taking that risk… going out to the wilderness to see John, because his message was reaching the population centers and something about it caused people to listen and to want to hear more.

It is, to us, odd that God trusted such an inappropriate carrier to deliver such a vital message. William Herzog, theologian and writer, wrote, “The Word of God came to a nothing son of a nobody in a godforsaken place.” And so, perhaps it is human expectations that might be modified. It is often in the godforsaken places that God’s presence is abundantly clear, and yet we may not recognize it.

Luke reminds us that the word of God might not appear in the places we expect it to be. It might be apparent in the places we least expect it. And perhaps then, in Advent, we focus, with intention, on those surprising, and often godforsaken places in which the word of God may be apparent. The word of God came to John in the wilderness – the places of anxiety and chaos, not necessarily in the high seats of power.

Years ago, I spent the good part of a year ministering to a young girl and her loving and devoted family. The child had the misfortune of a growing and debilitating illness in her kidneys. For weeks on end she and her family, her older sister and two parents, practically lived at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital in Seattle. Her death was a real possibility, and we all knew it. Though the doctors did everything they could for the child, they brought news one day to the family that the diseased kidney was no longer viable, and it would need to be removed, and, until a healthy donor kidney was found, she would need to be on dialysis. Through these dark days, her parents were in deep despair. Their beloved second child, their daughter, so horribly sick, and so weak. And the word of God came to John in the wilderness. In her weakness, in her wilderness, this little girl began praying. She may have heard us praying, but I believe it came from God and through her. She prayed for her loving and distraught parents, for her sister, who was, like her, missing a large portion of her childhood in those many hours spent in the hospital. The child prayed for the doctors and nurses in the hospital, and she prayed for the other sick children in the rooms near hers. Sometimes she prayed while she was awake, other times, her prayers came when she was asleep. At the depths of her illness and before the operation to remove the kidneys, she slept a lot and she began repeating a phrase that was hard to make out, it was so soft and quiet. “Love them…” she would whisper, an admonition, an unfinished prayer, with no amen, just the imperative, “love them.” It was open ended, a fragment, a call from the wilderness of her ongoing and deepening illness to love others. It was a blessing from the wilderness of her experience.

I will always be filled with gratitude at being part of a community that walked with, sat with, sang with, prayed with this family, and to report to you that, thanks to the donation of a kidney from her father, that child is now an adult, a mother with two adopted children. She lives in a different community, so I only see her on Facebook, but I see her sister occasionally, and feel an immediate bond, a loving cement to that community and that experience over those long months, and especially in the words “love all”, surely the word of God, that was an essential part of their family’s difficult experience and their ultimate healing – the word of God spoken to them in the wilderness.

From her hospital bed, with wires and tubes running into her tiny body, this child prayed prayers of intercession for those around her. Prayers can be for others, can give praise, can express agony and despair, and they can be made, as this story tells, in any time and in any place. The word of God came to John in the wilderness.

Wilderness experiences can come in many ways, at most any time in our individual or communal history. The deeply agonizing period of time in this country’s history that we know as slavery is one such time in our wilderness. The spirituals sung in those times were prayers of despair, prayers of agony, and haunting words of hope sung to each other. Words of God in places we would least expect them. The word of God spoken in the crucible of slavery – in the very places we would least expect them.

Last week we sang, “Soon and very soon, I’m going to see the King….” The enslaved sang to live. The word of God came through their voices and bodies there in the wilderness. "God’s going to trouble the water". . . "Deep River". . . Words in the wilderness . . . "WADE in the water" . . . words in the wilderness.

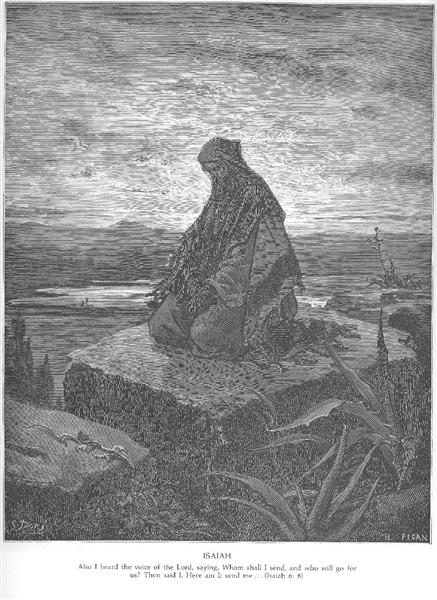

John quoted the prophet Isaiah, who spoke to those in the pain and sorrow of the wilderness of the exile, and he reminded them of God’s coming salvation: "Prepare," John said. "Prepare the way... all flesh shall see the salvation of God." God comes to us, like a salve and delivers us in the wilderness. The word of God comes to us in our own wildernesses. We each have them… places where we feel lost, alone, and wandering, times when nothing aligns with how it usually is, how we want it, where our hopes can’t quite be fulfilled, where we are lost, where our fears are. Illness, the end of a relationship, political turmoil, poverty in the world, worries – and actions that pull at our hearts and cause us to writhe. And God’s word comes to us in the wilderness. Your salvation is at hand.

As Advent breaks into our lives, into all that is--the hurt, the bold, the tender, the daunting, the extraordinary, the fleeting, the wilderness, the normal, the outrageous…the wilderness--Advent transforms it all by this audacious announcement from John. Everything--every thing--has been changed by the advent of Jesus Christ, the Son of God. Even the wilderness, that vast and unfriendly space, is filled with God’s presence, God’s love, God’s word. So, go then and love, do what is best for the most, embrace life in all, and then let go, because your salvation is at hand.

To close… part of Mary Oliver’s poem, “In Blackwater Woods”:

Every year

everything

I have ever learned

in my lifetime

leads back to this: the fires

and the black river of loss

whose other side

is salvation

whose meaning

none of us will ever know.

To live in this world

you must be able

to do three things:

to love what is mortal;

to hold it

against your bones knowing

your own life depends on it;

and, when the time comes to let it go, to let it go

The word of God came to John, comes to us, in the wilderness. Salvation.