“Stephen, full of grace and power, did great wonders and signs among the people.” (Acts 6:8) The patron saint of this congregation is, of course, Stephen, and because his feast day is the day after Christmas, it is more often than not overlooked. That’s sad, as it is a day that we should really celebrate. So today we are doing just that in the act of transferring his feast day to today. Rev. Mary and I would like to offer some insights into just who St. Stephen was, how this new icon can be experienced to gain further insights, and a few challenges of what we do with that knowledge.

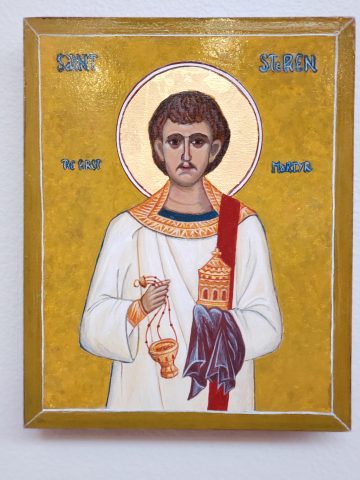

We are blessed to have an iconographer, as Mary is, in our congregation. She has done many icons that have added depth to our worship, but most recently, she has done two icons of Stephen: one that you see on the altar today and another of Stephen’s martyrdom. I have spent time with both, and I’d like to share a little bit of my own experiences with them, for I feel they should be viewed together. But first, some biographical information about him, of which we really have very little.

Stephen, the name, is from the Greek Stephanos, meaning “Wreath or crown” and, by extension, “honor and reward,” and was often given as a title rather than a name. We believe he was born in or near Jerusalem in about the year 5 CE and died in 34 CE at the age of 29, after having been stoned to death by men of his own faith. We know he was a Greek-speaking, educated, Hellenistic Jew, and was one of the first deacons. After his conversion to Christianity, Stephen took control of the alms-giving to elderly widows in his community. We know that Stephen was part of a group of seven Hellenists who were sent on a religious mission to go forth and preach Christ’s teachings and tell the story of his life, death, and resurrection—and so they went. Of the group, especially Stephen met with great success. In his bold preaching, he often criticized some of the aspects of Jewish Mosaic law, and this at first annoyed and then enraged many. After he had made some particularly hostile allegations, his Jewish listeners became outraged, and they brought Stephen in front of the Sanhedrin, the high council of Judaism, presided over by the high priest, who was, by that time, increasingly upset by what he perceived as Christian dissidence. After the questioning, Stephen was hauled out, and the mob stoned him to death, while Stephen prayed to God to forgive his killers for their sin. This was all with the consent and under the observation of Saul, a Roman Jew, who later converted and became Paul, the great Christian Saint. I wonder if this event was significant in Saul’s life and may have planted the seeds for his profound conversion experience later.

In my initial time with the Stephen icon, I have perceived both his youth and the weight of all that he bears. Stephen was a relatively young man when he died, but his death was brought on by the world’s reaction to his ministry—the ministry of bearing much of the weight of the world. The weight of service, the weight of the church, the weight of caring for and boldly speaking up for the poor and needy—all of that comes to me in the Stephen icon. As always, I am drawn to the light that radiates out of him in the reflective gold that surrounds him, and to the halo that represents his holiness. The icon calls me to engage with that holiness or set-aside nature, and how it relates to his humanity. And I wonder how Stephen’s attributes affect me and how I can be of support to other Stephens in the world.

The second icon of Stephen, not here today, portrays Stephen at the stoning. It is an icon of the Martyrdom of Stephen. It is powerful in its energy, with two figures hurling stones at Stephen, who is slumped on the ground looking up at the risen Christ whose arm is raised in blessing, and Saul seated, and passively watching, guarding the cloaks of the men who are casting the stones. As Mary points out, “In this one icon, the Martyrdom icon, is an image of what began to happen when the message of Jesus was taken up by Stephen. Yes, Stephen was martyred for proclaiming and living that same message, but his martyrdom planted the very seeds of Saul’s conversion.”

My interaction with this icon brings me the emotion of watching something so bad happen to someone who was trying to do good. It connects me with incidents like it in today’s world. It makes me wonder where it may be happening right now. Who is being stoned for the sake of good? Where am I in this icon? Am I casting stones or sitting on the rock like Saul, or have I run somewhere to get help? I expect you will see this icon sometime soon.

When our ancestors here at St. Stephen’s named this congregation after Stephen, I wonder why they chose the name. Some have suggested that the founding members of our congregation wanted to please the then bishop, The Right Reverend Stephen Fielding Baynes, by choosing his name. We have found nothing in all the records we have that indicates why the name was chosen. And so, we continue to wonder why and to let those thoughts continue to inform and identify us.

As this new icon is given, received, and will grace this worship space, we will experience it in many ways. It may lead us into discovering what God had for us in the naming of this congregation back in the 1950’s. I pray that it may challenge and strengthen our faith and bring us to new understandings of what it is to follow Jesus in our world today.

I have been asked to talk about my experience of writing the icon of St. Stephen. I was inspired by Harry Anderson’s homily last July 29, when he challenged us to commit to the transition process of change in anticipating a new rector and all that might mean for the future of this parish. It came to me while Harry was speaking that I would write— as iconographers refer to the painting process of icons—the icon of St. Stephen as my offering, my way of committing to the changes to come.

There are two types of St. Stephen icons: the one you are receiving today and the other, called the Martyrdom (or Stoning) of Stephen. I was particularly drawn to the Martyrdom icon, though I didn’t know at the outset why it was so compelling to me. So I decided to paint both types of icons simultaneously and just see what I would learn.

I must tell you, one of the major differences between icons and all other forms of religious art is that icons are not intended to be realistic images. Rather, icons consist of a symbolic language that is not meant to be taken literally. The symbols that make up icons go deeper into metaphor, and eventually into mystery. Icons do not give up their meanings quickly—a fast glance will only yield your own opinions—which, for me before I began studying iconography 15 years ago, was that icons were basically bad, unsophisticated art. I couldn’t have been more wrong. Icons require our full attention over time, and yield powerful benefits in proportion to what we bring to them. Icons demand a humble, contemplative process of learning to read their symbolic language.

Because icon symbolism is a foreign language to us in Western Christianity, a brief guide for all the symbols in the St. Stephen icon has been left on the table in the back where the icon will hang. I need to alert you to an error I made, in that I sent the wrong photograph for the bulletin cover. You may have already noticed that the bulletin image is a little different from the icon you see before you. That mistaken photo is of my first attempt, which I did not like, so I started over, producing the icon you see here:

I want to explain for now just the color symbols of Stephen’s clothing because, as in all icons, clothing are primary clues for the mystery. Stephen wears a white robe: in icon language, the color of martyrs and also resurrection. There is a narrow band of teal blue at the neck, indicating an inner garment beneath the white outer robe. Blue represents the color of humanity in icons. So the blue garment next to his skin means Stephen was first of all human, and then, at the end of his life, he put on the white garment of a martyr. (The Martyrdom icon shows the same clothing, revealing the blue sleeves of the undergarment.)

Neither icon answered my question of why Stephen became a martyr. What did he do that provoked such violence against him? The answer is found in Scripture, two chapters of the book of Acts, of which only a small portion was read today. To get the entire story, I started at the beginning of Chapter 6 and waded through Stephen’s truth-telling witness of Chapter 7— realizing its significance maybe for the first time ever. But it was the first few verses into Chapter 8 where I found the stunning postscript to Stephen’s martyrdom. Scripture, like icons, also requires more than a quick glance or cursory reading just to get information. Both icons challenged me to ask the same “why” question, and Scripture is where I found answers that I am still unpacking.

My experience in writing both icons brought me to a deeper engagement with a story I already knew at one level—my head mostly. But you don’t have to actually paint an icon in order to fully engage it. My hope in offering this icon is that over time the patron saint of this parish will become a role model for us. It is a huge risk to offer an icon to a congregation that is not used to icons and that may not be ready for it, because icons never pretend to be simply another form of religious art. You’ll be able to ignore this icon. Newcomers will probably not even know it’s there, off to the side in the back. Out of the way is a fine place to be, especially for something that is foreign and challenging.

But I expect you could engage this icon as the hospitable, welcoming people you are—the very character of this congregation—and become open to the process of learning what you don’t know about icons in general, and this icon in particular. You might start by just glancing at it when you enter and leave the church. You don’t even have to walk over to the icon; just begin by making a habit of checking to see if it is still there each time you enter this room. Simply getting used to seeing an icon in this worship space is an essential first step. And then, as you would with any stranger, walk over to it and acknowledge its presence in some way that fits for you. And, as you would with any stranger, accept that maybe God has brought this stranger here, for some reason you don’t know. Then, over time, you’ll learn about this stranger, this icon called St. Stephen, The First Martyr. Maybe you’ll come to know about St. Stephen in a way that differs from the way you’re used to learning. But, as with any stranger in our midst, it will take time to wonder and listen, time to question and reflect about what made this stranger as he is. It is a huge risk to welcome the stranger.

As it will be a risk to welcome the new rector. It will be up to each of us to decide how much time we’ll give him to become our spiritual leader. How much time will we give him our full attention, listen to him, learn his ways, and allow his presence here to have an effect on us?

The new rector will be here in a couple of months. Are you ready? Will you be able to receive him?

But the icon of St Stephen is here for you now. Are you ready to receive it?

The Rev. Mary E. Green